Beyond the planet: Charting the future of the space sector

With countries and companies racing to explore space, the sector is likely to see massive changes in the next 30 years.

Major events can unfold even within a single week: China has just become the second nation to plant its flag on the Earth’s moon, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos announced his space company Blue Origin will take the first woman to the moon, and Japan’s Hayabusa-2 capsule has returned safely to Earth with asteroid samples.

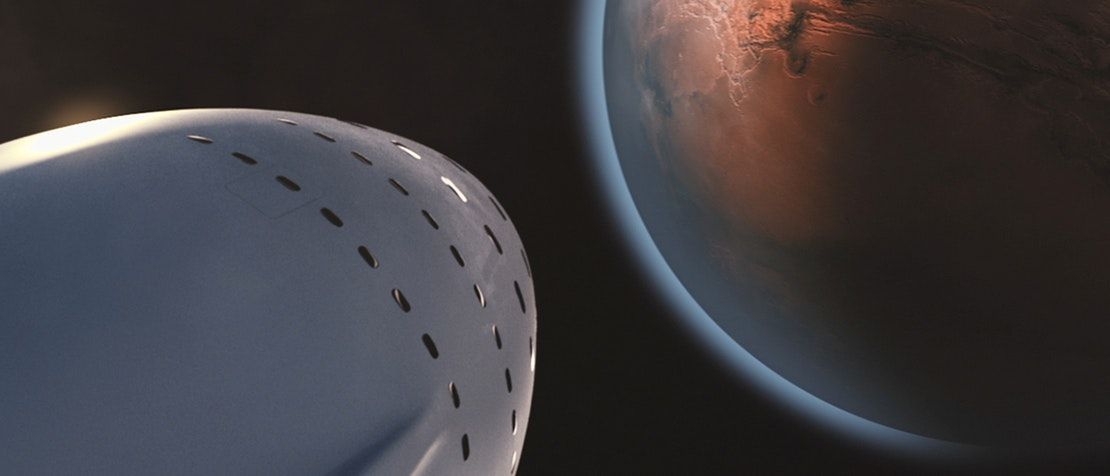

This buzz of space activity is unlikely to abate. SpaceX has launched nearly 1,000 small satellites for its Starlink constellation to date and is reportedly planning a crewed mission to Mars by 2026. NASA has also announced a mission to send astronauts to the moon by 2024 with plans to set up a lunar base camp.

In a panel at the virtual Web Summit 2020, astronomer Jonathan McDowell from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and Peter Martinez, Executive Director of the Secure World Foundation, looked at where the space industry might be 30 years from now.

Who will be the space traffic cops?

“We are at the beginning of a new [space] investor revolution,” said McDowell, noting the number of active satellites has been skyrocketing.

“The rules of the road are not set up for these satellites,” he asserted, estimating we could see about 100,000 satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) within the next decade.

While the use of radio frequencies in outer space has been regulated since 1963 within the ITU framework, space traffic management (STM) does not exist for the current scenario, McDowell explained. In this new space environment, routes must be managed to avoid accidents.

The dangers of overcrowding in space were flagged by NASA scientist Donald Kessler in 1978. The so-called “Kessler Syndrome” warned that one day the low Earth orbit would become so crowded with satellites and debris that it would lead to frequent collisions that impede space explorations.

More than 40 years later, Rocket Lab CEO Peter Beck has warned how his company was finding it difficult to make a clear path for its rockets to launch new satellites. McDowell believes there is a need for an international body to manage this space traffic problem.

“Space is intrinsically global, so it has to be at the UN level,” he said.

The Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) was set up by the UN General Assembly in 1958 and currently serves as a capacity building resource for countries to expand their space capabilities and accelerate sustainable development through space.

“Individual countries can sign up for a sensible rule because we all want to get along. It’s not enough for the US to have its space surveillance. There has to be an international committee,” McDowell added.

Martinez agreed that STM will have to be addressed at a global scale. “Problems will begin at the national level. And best practices and development of regulations at a national level will be a good model. The UN is certainly a good forum of socialization,” he added.

Martinez noted the debate underway about whether these changes must follow a top-down or bottom-up approach. “The UN Committee will play a part in this. Elements foundational to STM are under discussions in the Committee even though those are not a part of it,” pointed out Martinez.

Looking ahead to 2050

Activities in space have rapidly evolved compared to the first 50 years of exploration, said Martinez. With diverse actors, the kind of events taking place now did not exist a decade ago.

Activities like servicing and refuelling [satellites] while in orbit will be foundational in the development of the space economy, he added.

Martinez also surmised that the future might be seeing greater use of space by militaries. In a meeting of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space in 2019, it was noted that “preventing conflicts in outer space and preserving outer space for peaceful purposes” is more necessary than ever.

Martinez put forth the different scenarios likely to emerge in the future. For him, the two dominant forces to consider are cooperative governance and commercial space.

He likened the scenario where cooperative governance and commercial space flourishes to the epic Stanley Kubrick film ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’. “We will have a destiny in space and in the solar system like in the movie, with a space economy worth trillions of dollars and contributing to [global] GDP,” said Martinez.

But if the commercial space sector evolves more rapidly while cooperative governance lags, [then] the situation will be akin to the film ‘Elysium’ where space is full of opportunities but only for the few, Martinez warned. Actors here will be driven by their self-interest, he added.

According to Martinez, while governance issues might be sorted, a third possible future in space does not unfold because of climate change. The fourth scenario, Martinez concluded, sees governance issues being ignored and military confrontation extending into space, further exacerbating the space debris problem.

“We are in that second commercial-dominated track now,” suggested McDowell. Commercial activities had been negligible until the end of the Cold War and have exploded in the past few years, he noted. “Unless governance starts to happen quickly, we will be in that irredeemable ‘free for all’,” McDowell warned.

Martinez called the first scenario the “optimistic, inclusive and expansive track for humanity in space”, noting that commercial space exploration “is not a bad thing. It is a good thing.”

The best possible future is that governance keeps pace with commercial space, Martinez said.

This scenario will come to fruition, he added, when states begin to accept dangers of conflict in space, adopt voluntary testing in low Earth orbit and practice cooperative space traffic management.

Responsible space solutions

McDowell called for a debris committee composed of experts from different space agencies. “Establish norms that can then be taken up at the governance level,” he advocated.

Martinez added that beyond norms, there was a need for multi-faceted regulatory and behavioural solutions. For instance, he called for venture capitalists that practice responsible investment in space. “So we don’t have people rushing in to invest in constellations when you have satellites in orbit that are not being used or controlled,” he said.

This absence of rules related to the physical positioning of satellites in space is in sharp contrast with the existing ITU rules contained in the Radio Regulations about the management of radio frequencies in outer space.

Factors such as planetary protection, space environment and public pressure will be important to make this happen, said McDowell. When asked about discoveries and searches for microbial life in the solar system, both experts highlighted the importance of protection and responsibility.

“This is an ethical question. We need to be careful and make sure to even sterilize space probes,” McDowell said, calling for caution when deciding on destinations in the solar system to explore or protect.

“Finding other life will be a watershed moment for humanity. It will prove once and for all that we are not alone. It will have a profound effect on society and the way we see ourselves in the universe,” said Martinez.

ITU encourages anyone working on space-related activities, from research to commercial ventures, to get involved in the activities of the ITU Radiocommunication Sector, either through their national delegation or by seeking membership for direct participation.

Watch the ITU Satellite Webinar series for the current technical and regulatory situation, evolution, and trends in the field of satellite communications.

Image credit: SpaceX via Pexels