ICT infrastructure remains one of the key things to focus on in order to bring everyone online by 2030. ICTs can help countries leapfrog chronic development impediments in areas from education and health to government services and trade. ICT services make businesses more efficient and productive, as they open the door to innovative services and applications that can fuel growth and trigger new opportunities.

ICT infrastructure is an essential component for a digital economy, as it comprises the facilities for transporting, exchanging, and storing data. There are significant gaps in national transmission networks, Internet exchange points (IXPs), and data centres. The coverage and density of national transmission networks are lagging in the developing nations. It is also important to have a streamlined network licensing process, and these are often lacking.

Key issue: Economic stimulus for deployment of ICT network (terrestrial and space-based)

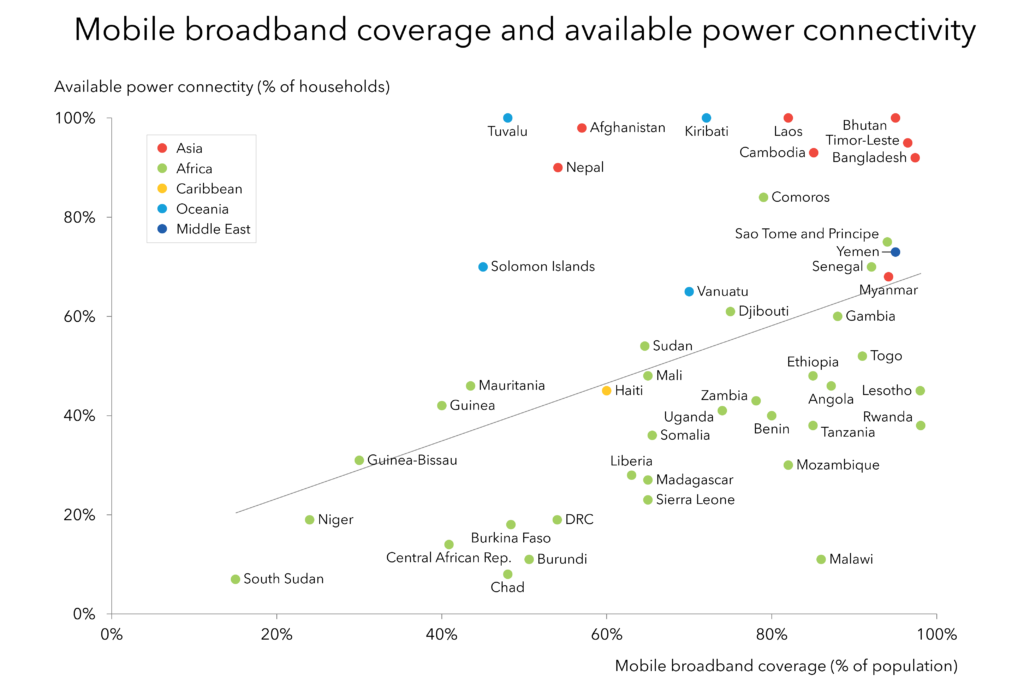

From Figure 6 it is evident that African LDCs require more digital infrastructure, for both mobile connectivity and power.

The deployment of ICT networks in the LDCs and developing nations remains a challenge due to a multitude of factors including:

- High costs to deploy the network

- Small population/market size, making it difficult to exploit economies of scale

- Insufficient government policies and regulations, as well as weak overall stability

Potential interventions:

A) Active and passive infrastructure-sharing

Sharing network resources (wireline and wireless), backhaul, spectrum and fibre across sites brings in synergies and reduces network build costs. This can make the infrastructure deployment more economically viable. In many countries, regulatory bodies have given the go-ahead to communication service providers (CSPs) to engage in active and passive infrastructure-sharing. Similar regulatory measures would be especially beneficial in rural and remote areas. Furthermore, joint action by CSPs to implement the modalities stipulated in sharing agreements will further streamline the deployment of ICT networks.

Incentivizing passive infrastructure-sharing at the government level can be a key enabler and the CSPs can voluntarily engage in promoting this concept. National governments can provide technical assistance to municipalities and encourage the development and updating of local regulations that promote infrastructure-sharing, including simplified permitting processes for small cells and macro sites, and a radius of non-proliferation.

Spotlight

Telefónica has struck deals in Brazil, Mexico and Peru, while CNT and Claro have signed an agreement in Ecuador. Infrastructure sharing helps to reduce unnecessary duplication of network infrastructure, saving costs and speeding up network roll-out.[11]

Spotlight

The Inter-American Development Bank published a document analysing the benefits derived from sharing as well as its regulatory and legal implications. The document presents potential models for implementing this strategy in Latin America and the Caribbean. According to the Bank, infrastructure-sharing has the greatest potential “to reduce the cost of deployments and thus make private sector investment in infrastructure-sharing viable, both among telecommunications operators and with operators of other infrastructure (electricity, roads, and gas, among others)" [12]

B) Business case

A shift towards longer-term horizons on infrastructure investments by private players would enable greater financial returns. This would also allow CSPs to cover the offline, hard-to-reach geographies and last-mile gaps. Policies, subsidies, standard operating procedures (SOPs), universal service obligations (USOs), and best practices can help improve business cases. Other key aspects to consider are the social return and the contribution to sustainable development, which is becoming increasingly important.

Spotlight

Indonesia’s Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, via its USO agency (Badan Aksesibilitas Telekomunikasi dan Informasi), has a five-year agreement with Teleglobal and SES Networks to supply 150,000 sites in remote areas of the country with broadband Internet access and mobile backhaul services.[13]

C) Faster and more economical deployment

Enabling the ecosystem to build faster and at a competitive price is fundamental to achieving universal connectivity. Another key enabler is the availability of data and the mapping of existing network infrastructure to identify white spaces and prioritize coverage; also important is the sharing of information between the public and private entities to bring synergies in the effort to deploy ICT networks. Private parties or government agencies can ensure the availability of disaggregated data for creating national strategies and effective network deployment roll-out plans.

Spotlight

Why is broadband mapping key to universal connectivity? Watch the video and click on the ITU Interactive Maps to track connectivity around the world. The maps document over 20 million km of terrestrial networks. They support initiatives like Giga, a joint project by ITU and UNICEF to connect all the world’s schools. Policy-makers, investors and network providers use broadband maps to make faster and more accurate decisions.

Spotlight

As part of the WARCIP-Mauritania Project funded by the World Bank, the Mauritanian government has succeeded in building a national backbone of 1,700 km of optical fibre linking several regions of the country. This project was carried out through a public-private partnership.[14]

Streamlining processes to facilitate wireless and wireline communication networks and making sufficient spectrum available for a wide array of ICT technologies (terrestrial and space-based) and services are all key actions to speed up deployment cost-effectively. It is imperative to note that global coverage, with an adequate quality of service, should be prioritized over speed to avoid broadening the digital divide. However, the network needs to align with what the government defines as the basic minimum broadband speed for each user.

D) Neutral passive infrastructure

Opening the passive infrastructure roll-out to neutral parties can be beneficial as it allows faster progress and enables competitive pricing of the infrastructure. This allows the deployment costs to then be optimized. The introduction of regulations to remove the barriers facing passive infrastructure providers, particularly in countries where state-owned operators are the only providers, is a way to unlock this leverage.

Spotlight

Liquid Intelligent Technologies has deployed more than 100,000 km of backbone fibre in Africa. This group first installed fibre in 2009, and now owns the largest independent fibre network on the African continent. By expanding into the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Liquid introduced fibre to a population that only had access to expensive mobile broadband [15]

Spotlight

UFINET is a neutral fibre-optic operator in the wholesale telecommunications market. They provide capacity services and connectivity through a fibre-optic network linking together Latin America, Mexico and the USA.[16]

E) Community collaboration and deployments

Having the necessary licence and security aspects in place to allow public and private players to operate community Wi-Fi services may go a long way toward expanding the reach of Internet accessibility. This requires support from regulators to create a conducive environment, as well as private players who are willing to deploy the networks. In a community collaboration model, a community rolls out the last-mile network and takes responsibility for its maintenance. The network is usually composed of simplified small cells, and satellite-enabled cellular or Wi-Fi sites, which are relatively easy to activate and maintain. Community involvement in the deployment and maintenance of the network results in lower costs for the operator, thus increasing their willingness to set up networks in rural areas. In an alternative version of this model, governments can allow an operator to count community networks towards its coverage obligations, and in exchange, the operator can provide backhaul at a reduced cost.

Spotlight

The BharatNet Scheme 2022, launched by the Indian Government, is the world’s largest rural broadband connectivity project. It aims to equip 250,000 Gram Panchayats (village councils) and 600,000 villages with high-speed digital connectivity at affordable prices. The councils run Wi-Fi networks to provide Internet to the local community. [17]

Spotlight

Zenzeleni Networks is a Wi-Fi-based ISP in South Africa that provides affordable voice and data services. (Zenzeleni means ‘do it yourself’ in Xhosa.) Its networks are managed by people in the local community, and customers can use Wi-Fi-enabled devices to access its services. It has provided Internet access over a 30 km radius in the Mankosi community and is on track to connect 300,000 people in up to 30 villages in the region. [18]

Key Issue: Energy availability

Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this [map/infographic] do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ITU and of the Secretariat of the ITU concerning the legal status of the country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries

As shown in Figure 7, most developing nations find it difficult to meet current and future energy demands and provide universal access to reliable and affordable energy for domestic and commercial use.

According to the World Energy Trilemma Index 2021 Report, most African nations lag considerably behind the rest of the world in terms of energy equity (the ability to provide reliable, affordable and abundant energy) and energy security (the ability to meet current and future demands for energy). Africa has a score of 46 out of 100 for security and 26 out of 100 for equity. Asia fares better, with an energy security score of 58 out of 100 and an equity score of 68 out of 100. This poses a massive challenge when it comes to the large-scale deployment of ICT infrastructure and people’s ability to use relevant digital devices.

Potential interventions:

A) Reliable and sustainable energy

Reliable and sustainable energy interventions are imperative in meeting the need for expanding ICT infrastructure. Governments are investing in increasing the energy index, which measures on one hand the energy equity to ensure universal, reliable, affordable and abundant access; and on the other hand, the energy security to meet current and future demands. Simultaneously, they can leverage the ICT infrastructure to meet some of the demand. Tower companies can be encouraged with attractive policies and subsidies to use renewable energy sources (e.g. solar) and offer power to communities, increasing their energy access and security.

Spotlight

Internet Para Todos (IPT), a broadband-focused rural towerco in Latin America, aims to establish 3,600 solar-powered small cell sites to achieve last-mile mobile connectivity across Peru. The solar hybrid systems are deployed using four models: capex, opex, energy savings as a service, and energy efficiency service.[20]

Spotlight

Airtel, India’s premier communication intervention provider, recently commissioned a captive 20MW solar power plant in partnership with Avaada. The plant will supply clean energy to Nxtra (Airtel’s service arm for its edge data centre).[21]

B) Micro-energy grids

Micro-grids as self-sufficient energy systems may potentially provide a solution to low electrification rates across the developing nations including the LDCs, LLDCs and SIDS. A micro-grid is “a local energy grid with control capability” that can work autonomously to both produce power and supply it to remote communities. [22] Small and often isolated, micro-grids have the ability to easily harness renewable energy sources and could constitute at least part of the answer to the electrification problems. The autonomy of micro-grids means that they avoid some of the negative aspects of larger power grids, such as rolling blackouts. In many developing nations, governments are eagerly implementing micro-grid technology in areas without pre-existing infrastructure.

Spotlight

Energicity builds, owns and operates solar-powered micro-grids for off-grid communities with more than 100 households. These micro-grids provide 24-hour electricity to communities using solar and battery storage. The company distributes AC electricity to its end customers metered at each individual household. Energicity’s electricity is affordable, reliable and scalable. Those micro-grids serving rural communities operate through subsidiaries in Ghana Sierra Leone and Nigeria, and currently serve 36 communities and 23,000 people.[23]

Key Issue: Use of multiple technologies

One of the key issues in expanding the coverage of high-speed connectivity across different geographies has been the dependence on expensive traditional technologies. The deployment of these technologies is capex-intense and highly time-consuming. New promising technologies can become key enablers, especially for geographies where expanding connectivity to hard-to-reach areas, like extremely rural areas or islands (SIDS), remains logistically and financially unviable.

Potential interventions: Choosing the most effective technological intervention

While last-mile mobile and fibre networks will continue to be the mainstay of ICT network deployment, space-based technologies are now part of the mainstream. Satellite broadband communication is becoming a major enabler of providing connectivity and Internet services. Many private players are launching satellites in geostationary satellite orbit (GSO) and non-geostationary satellite orbit (NGSO) segments. Going forward, it will be important to integrate mixed-technology landscapes in national strategies/plans, streamline the licensing procedure for satellite broadband spectrum availability, and make policy changes to foster growth.

Satellite connectivity is cost-competitive for remote and dispersed populations where fibre deployments are challenging. The new generation of LEO and high-throughput GEO satellitesare likely to lower the cost structure even further. Satellite users are expected to multiply 2.5 times by 2029, and 90 per cent of these new users will be in emerging regions [24]

"Satellite communications are everywhere but all too often remain invisible to the general public."

- Mario Maneiewicz (Director, ITU Radiocommunications Bureau)

Combining satellite broadband communication with other technologies has the potential to solve some of these issues; however, but it is not yet being deployed on a large scale. Satellite connectivity along with terrestrial networks can enable the development of an extensive gateway infrastructure which can then act as a hub for providing multiple services like community Wi-Fi and MSME connectivity.

Spotlight

Schools in Kenya are being connected with 100% coverage by iMlango through Avanti’s satellites. iMlango is also providing the schools with a learning platform and interventions. To date, 180,000 children have benefited from this. [25]

Spotlight

With customers relying on their mobile network for their very livelihood, Tigo Tchad required a partner who could quickly refurbish 40 of their cell sites and establish an in-country teleport with limited downtime. SES completed the upgrades and teleport construction in less than four months, despite the physical challenges involved. This intervention utilizes SES’s GEO capacity for ease of deployment and broad coverage of all locations. [26]

Spotlight

Orange Mali selected Intelsat to bring 3G and 4G connectivity to hard-to-reach areas in Mali, the eighth-largest country in Africa. Mali has a population of just over 20 million people. [27]

Key Issue: Spectrum availability and management

The availability of spectrum undergoes a cumbersome process of identification, clearance, technology definition and restrictions, valuation, and awarding. Each country has its own set of challenges and issues across each of these categories. Some of the key challenges with spectrum management include:

- reserve prices that may be well above market valuation;

- a scarcity of, or unclear policy on, spectrum availability; and

- the awarding mechanism being too lengthy, complicated or inappropriate.

Potential interventions:

A) Spectrum allocation

Spectrum is a key but scarce resource needed for the deployment of ICT services. It is essential that proactive steps are taken to enable the objectivity of universal connectivity, particularly with regard to spectrum. Effective spectrum management has a direct bearing on the quality and affordability of mobile services. Management activities that can be undertaken include:

- allocating a sufficient amount of internationally harmonized spectrum for IMT;

- ensuring that there is a balance in allocations between licensed, license-exempt, and satellite IMT; and

- working through the ITU Radiocommunication Sector to ensure that there are appropriate rules to mitigate interference while minimizing constraints on the deployment of services.

Spotlight

The African Telecommunications Union (ATU, a specialised agency of the African Union) and key industry players developed a set of policy recommendations to improve access to information infrastructure and services. These recommendations included spectrum licensing, spectrum evolution, spectrum management, and emerging radiocommunication technologies. [29]

Spotlight

Spectrum allocation is one of the outcomes of the PRIDA project which is being implemented by ITU-BDT in Africa. This project, funded by the EU and ITU, is about understanding international spectrum pricing, defining roadmaps for current and future spectrum needs, outlining realistic coverage and quality guidelines, and unlocking unlicensed spectrum to enable future technologies. These are all key actions for better utilizing spectrum. [30]

Key Issue: Availability of adequate infrastructure to provide meaningful connectivity

Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this [map/infographic] do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ITU and of the Secretariat of the ITU concerning the legal status of the country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries

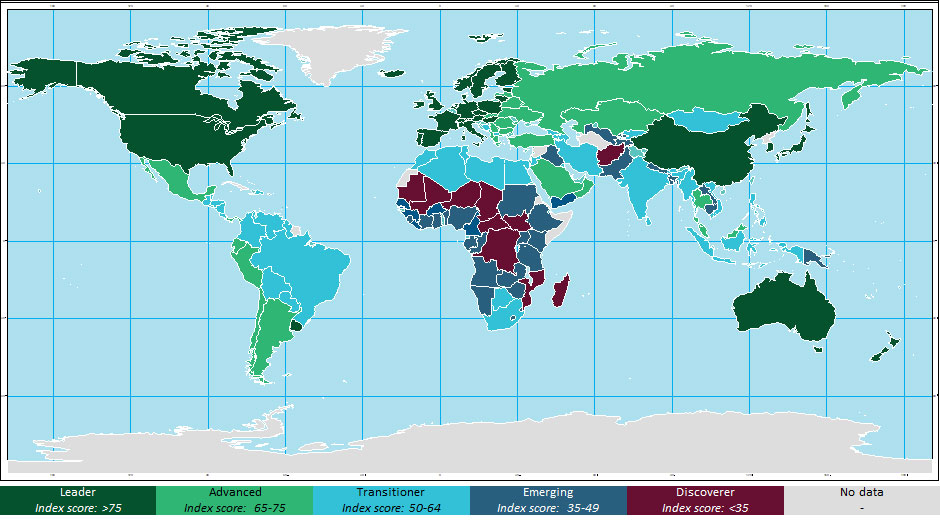

On one end, the challenge is that a large portion of the population still remain unserved by the ICT infrastructure; however, for people who are covered, a key dimension to having connectivity is for it to be “available for everyday use, accessible and fast, relevant with enough data, affordable, safe, trusted, user-empowering and leading to positive impact”.[32] In Figure 9, countries are grouped based on the advancement of key enablers for mobile Internet adoption, which includes infrastructure, affordability, consumer readiness, and content and services. The meaningfulness of connectivity is considered in section 2.2 with a special focus on LDCs.

Potential intervention: Policy, legal and regulatory measures

Policies and regulations stipulating key criteria (e.g. minimum speeds to qualify as broadband, basic standards for safe and trusted connections and user empowerment, and pricing control for devices) are required to outline an avenue for “meaningful connectivity”. These need to be aligned with national digital strategies and roadmaps defined by governments. To successfully implement both policies and strategies as well as ease approval processes and decision-making, strong inter-departmental coordination by governments and in the public-private partnership (PPP) environment is imperative. In addition, adapting public financial instruments to new business models of ICT (e.g. cloudification) will be an important enabler. It is also critical to consider that while general principles may be similar, there is no fit-for-all intervention. The approaches and interventions must be tailored to the specific country’s needs and reality on the ground.

Spotlight

To support countries with ensuring that their populations have meaningful connectivity, the Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI) launched the Meaningful Connectivity targets and detailed policies informed by their research, analysis and multi-stakeholder consultations. [33]

Commit to a pledge on our Pledging Platform here. See guidelines on how to make your pledge in Pledging for Universal Meaningful Connectivity and examples of potential P2C pledges here

Footnotes

[10] ITU. (2021). Connectivity in the Least Developed Countries: Status report 2021

[11] GSMA Intelligence. (2021). Global Mobile trends 2021 Navigating Covid-19 and beyond.

[12] Inter-American Development Bank. (2020). Digital Transformation: Infrastructure Sharing in Latin America and the Caribbean.

[13] Telecom Asia. (2019). Indonesia’s Teleglobal acquires capacity on SES-12.

[14] WARCIP Mauritanie. (2022). Project de Connectivité Nationale

[15] Connecting Africa. (2021). Liquid Intelligent Technologies surpasses 100,000km of fiber.

[16] Crunchbase. (2022). Ufinet.

[17] Bharat Broadband Network Limited. (2022). BharatNet.

[18] Association for Progressive Communications. (2020). Zenzeleni Networks NPC.

[19] World Energy Council. (2021). World Energy Trilemma Index 2021 Report

[20] GSMA. (2020). Renewable Energy for Mobile Towers: Opportunities for low- and middle-income countries.

[21] Airtel. (2022). Airtel: PV Magazine. (2022). Avaada commissions 21 MW captive solar panel plant for Airtel.

[22] The Borgen Project. (2020). Microgrid Technology in African Countries.

[23] Tech Crunch. (2020). Could developing renewable energy micro-grids make Energicity Africa’s utility of the future?

[24] Buchs, D. (2021). Market Overview – Satcom for Universal Broadband Access.

[25] Avanti. (2018). Project IMlango.

[26] SES. (2019). Tigo Tchad.

[27] Via Satellite. (2022). Orange Mali Taps Intelsat for 3G and 4G Connectivity.

[28] GSMA. (2021). Spectrum pricing and licensing in Africa – driving mobile broadband

[29] African Telecommunications Union. (2021). ATU-R Recommendation: Relating to Spectrum Licensing for Mobile/Broadband Systems.

[30] ITU. (2022). Policy and Regulation Initiative for Digital Africa (PRIDA).

[31] GSMA. (2019). Mobile Connectivity Index.

[32] A4AI, GSMA and ITU definition

[33] A4AI. (2022). Meaningful Connectivity – unlocking the full power of internet access.