Key issue: Gender inequalities

In LDCs, LLDCs and SIDS, one of the greatest obstacles to comprehensive connectivity and Internet usage is the gap in gender demographics. Figure 16 illustrates how LDCs and LLDCs fare well below other nations, with only 19 and 27 per cent of women being connected, respectively. While 83 per cent of women own mobile phones, they are 15 per cent less likely to own a smartphone than men in low- and middle-income countries.[68] In the same geographies only 58 per cent of women use mobile Internet; however, 234 million fewer women than men are accessing it.[69] Women who own mobiles also use them less; on average, they have cause to use them 3.3. to 7.1 times per week, but men average 3.8 to 7.7 times.[70] These inequalities are driven by lower digital literacy rates and skills, less affordability, a wider pay gap, weaker safety and security measures, and restrictions on women’s activities stemming from traditional gender norms and stereotypes.

Potential intervention: Implementing policies to enable equitable access

Policies are required to tackle the two closely linked key drivers of gender inequity: existing socio-economic structures, and limited access to digital technologies. Governments should persist with addressing poverty, low education rates, restricted access to labour markets, and gender stereotypes that have created inequalities. To help lift LDCs, LLDCs and SIDS out of poverty, several systemic issues need to be addressed. Specifically, secondary school and tertiary education for women and girls is an imperative for sustainable change and requires the removal of structural barriers – including a lack of safe transportation, clean water for sanitation and hygiene (WASH), and safe toilets for individuals who menstruate starting at puberty. Moreover, societies’ attitudes and behaviours that drive inequalities, especially those of men and patriarchal societies, need to be changed. Tackling these problems will put women and girls in a better position to harness the opportunities made available by digital technologies. They can benefit from targeted training to develop their digital capabilities and opportunities to leverage technology outside of training that help build their confidence. Multi-sector partnerships can strengthen the execution of policies and strategies. Throughout the design, implementation and monitoring of all initiatives, it is crucial that women are a part of the leadership as well as being actively involved and engaged.

Spotlight

To ensure an increased uptake of digital technology, Prospera Digital in Mexico provides pregnant women and new mothers with health-related information using a conditional cash transfer model. The women receive this information via SMS messages, creating an opportunity for them to develop their mobile phone and SMS skills. [72]

Spotlight

The Action Coalition on Technology and Innovation, which is one of the six action coalitions under the Generation Equality Forum, is committed to developing “innovative, multistakeholder partnerships” to help achieve gender equality. The coalition consists of 15 leaders from civil society, governments, and the private and social sectors implementing a 5-year plan focused on reducing “gender digital gap”, making “technology feminist”, building “transformative ecosystems”, and “leaving no space for online violence”. [73]

Key issue: Inaccessible digital technology for persons with disabilities and older people

Not all digital technologies are designed to meet the needs and abilities of all people. Older people are more likely to be offline than those who are younger.[74] Persons with disabilities are between 11 and 55 per cent less likely to have a mobile phone than those without a disability.[75] Furthermore, they are less likely to own a smartphone or access the benefits of its AT, and their mobile Internet usage ranges from just 4 to 43 per cent.[76] Devices, software and platforms are not always available in accessible formats, which creates a barrier. As a result, people with hearing and visual impairments experience communication challenges, social exclusion, high dependency and a lack of information about services. People with physical impairments may struggle to use devices or navigate content effectively and face similar outcomes. Even as digital technology becomes more accessible, there are still difficulties with accommodating the varied abilities of older people and individuals with disabilities.

Potential intervention: Universal inclusive design, AT and policies

To ensure the digital inclusion of people with disabilities, older persons and other marginalized groups, ICT should be centred on universal design. This approach aims to create new technology that is accessible to everyone irrespective of disability, age, gender, ethnicity or any other characteristic. Universal design is underpinned by seven principles:[77] equitable use; flexibility in use; simple and intuitive use; perceptible information; tolerance for error; low physical effort; and size and space for approach and use.

AT is another pathway to achieving inclusion. Even with largely inclusive technology, some people are still likely to be excluded. For them, it is imperative that AT is developed to address the obstacles they face. The design can be low-tech or high-tech, and may harness special hardware or software, and tailored learning materials or devices. AT should be available at no cost to the user in order to ensure equitable access. Another enabler of accessible AT is open assistive tech and content, which is explored in more detail under Relevant and local content and services. It is also worth noting that persons with disabilities, older people, and their families and caregivers may need training to increase their awareness of AT and learn to use it effectively.

Inclusion can also be fostered through policies and strategies that governments introduce to help remove the barriers restricting these individuals from accessing and using digital technology. These policies should be developed from the outset either by or in consultation with older persons and people with disabilities, together with other key stakeholders. Alignment with the UNCRPD, where applicable, is advised. Policy should be implemented at all levels of government, from a national perspective to the local administrations. It is important that government portals incorporate, recommend, and demand these principles across every level. National governments can develop guides of accessibility and usability as well as provide technical assistance in the matter.

Spotlight

By offering online products and consulting to customers, a Mexican company called HearColors aims to ensure that websites, online platforms and applications are accessible to all users in Latin America. The company offers training on this for designers, developers and content creators; diagnostics to assess the accessibility of content; and a Web Access badge to validate websites that meet content accessibility guidelines. [78]

Key issue: Insufficient and ineffective child online protection

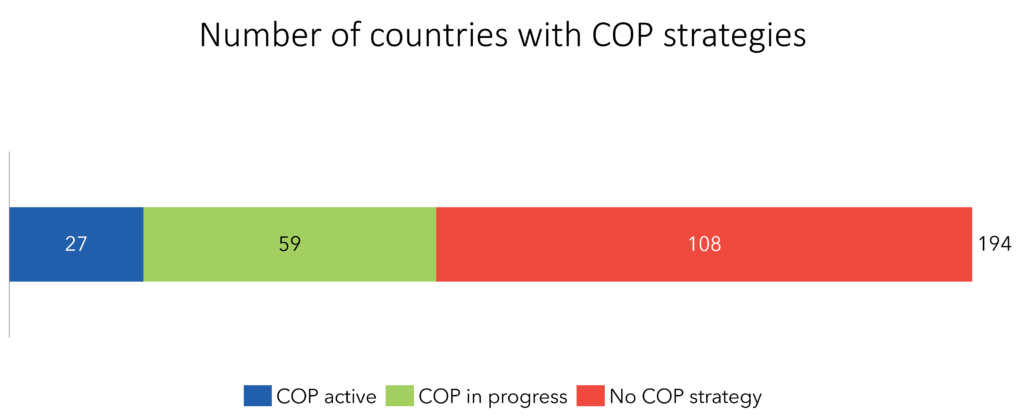

An increasing number of children and young people are connecting for the first time as access to the Internet and digital technology becomes easier and more widespread. Although ICT has allowed children and young people to communicate, socialize, share, learn, find information and express themselves on numerous social issues, it also presents the global challenge of protecting them while online. Being online makes them vulnerable to numerous threats such as identity and data theft, violation of privacy, harmful online content, cyberbullying, harassment, exploitation, grooming and sexual abuse. In 2020, more than 33 per cent of young people in 30 countries were reported to have experienced cyberbullying.[79] Additionally, the registered number of reports of suspected child sexual abuse material (CSAM) increased fourfold from 1 million in 2019 to 4 million in 2020.[80] There are still too few national COP strategies globally. As shown in Figure 17, over 100 countries have yet to start building, creating, or adopting such a strategy.

Potential interventions:

A) Education and strategies

As technology continues to advance quickly, the approach to strengthening COP needs to be adaptive and agile. Protecting children and young people from harm online requires minimizing four types of risk:

- Content risks: exposure to inaccurate or incomplete information, inappropriate or even criminal content, racist or discriminatory ideas, and content related to self-abuse, self-harm, destructive and violent behaviour, or radicalization

- Contact risks from adults or peers: harassment, sexual abuse, exploitation exclusion, discrimination, defamation and damage to reputation

- Contract risks: exposure to inappropriate contractual relationships, embedded marketing, online gambling, and the violation and misuse of personal data, and other issues around children’s consent online

- Conduct risks: the sharing of self-generated sexual content or risks characterized through hostile or violent peer activity

Mitigating these risks requires educating children and young people as well as their families and caregivers about COP. Similarly, legal and medical professionals need more education, awareness and readiness on COP to provide better support. Resources and tools must be made available to facilitate the development of the necessary digital skills and digital literacy to help tackle online safety. Governments can contribute to COP through inclusive multistakeholder strategies. These national strategies should be aligned and integrated with existing policy frameworks for children’s rights and cover all risks and potential harm to guarantee a digital environment that is safe, inclusive and empowering. Moreover, people should be made aware of what constitutes legal and socially acceptable behaviour online, and what actions must be taken to identify perpetrators and remediate the situation.

Spotlight

To make the Internet a safer online environment for children, MTN blocks sites with CSAM identified by the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) by using a neutral third-party software. Customers and civil society organizations are encouraged to flag online CSAM through the IWF’s confidential reporting portal. [82]

Key issue: Online antisocial behaviour and less online safety of vulnerable groups

An ongoing challenge for countries to address is online antisocial behaviour. This includes online harassment, racism, xenophobia, exploitation, sexual abuse and cyberbullying. In Latin America, safety and security has consistently been among the top barriers to mobile Internet adoption.[83] Certain groups of people, typically vulnerable groups, tend to have greater exposure to these behaviours and risks due to e.g. a lack of education, traditional or cultural prejudices, or extremism. For example, one of the top three barriers preventing women who are aware of the mobile Internet from using it is safety and security.[84] Other vulnerable groups such as the LGBT+ community, abuse survivors, and people living in poverty or with illness, mental health difficulties or addictions, may also be exposed to negative and harmful experiences online. These experiences can lead them to reduce or stop their engagement with digital technology. Antisocial behaviour has the potential to influence other users’ comfort with connecting as well. As technology continues to expand, so too will the risks that vulnerable groups face online.

Potential intervention: Regulations, reporting and education to safeguard online environments

Creating an online environment where vulnerable groups can obtain access safely will require contributions and collaboration from multiple stakeholders, including governments, private sector actors, and civil society organizations. Governments can develop and implement regulatory frameworks that seek to protect the rights of all online users, including vulnerable groups. These should be supported by putting processes and systems in place to respond to any violations (e.g. national CIRTs/CERTs). Some countries, as shown in Figure 18, have even adopted legislation that criminalizes online harassment and abuse. In alignment with regulatory frameworks, private sector organizations can integrate safety features in their products and services that mitigate the potential threats and risks faced by users. When people experience online antisocial behaviour while using these products or services, there should be a clear, simple and effective reporting procedure available to address the incident. For children, helplines and hotlines can be opened so that they are able to report incidents and obtain support. All connected people should be educated about their rights, empowered with information about how to keep safe online, and taught to leverage technical settings and other mechanisms to report antisocial behaviour. They also need to be made aware of illegal activities to avoid and given guidance on how to engage online respectfully and create an inclusive environment for all.

Key issue: Lack of data

There is little data about the estimated 2.9 billion people who are still offline, particularly in LDCs, LLDCs and SIDSs. Disaggregated and granular data tends to be even more scarce. Some barriers to obtaining data are the associated complexity, cost and time-frame. Another obstacle is the methodological development and alignment of the data collection procedure and the selection of indicators to track inclusion. When data is available, there is limited statistical capacity to interpret it. Without robust information, it is difficult to develop a comprehensive overview of the status of ICT and connectivity in these countries. The public, private and social sectors are unable to quantify the gaps in meaningful connectivity, making it impossible to realistically set targets, monitor and track progress, measure the impact of interventions, and identify actions that do and do not work. Furthermore, data often serves the interests of people who are in power instead of those who are marginalized. Existing power structures are maintained and even strengthened by the failure to enable people to generate and utilize their own data.

Potential interventions: Dedicated expertise, time and funds

Organizations across all sectors can contribute to collecting, verifying, harmonizing, analysing and sharing data individually or through partnerships. Increased investments in the funding and time required to collect and analyse data are key, as is improving the technical expertise and capacity of the regulators and operators. As their capabilities expand, there are greater opportunities to advance data collection (e.g. harnessing big data and AI) and introduce new statistics that are more accurate, granular, faster and cheaper to compute. In addition, organizations can contribute by thoroughly monitoring and reporting the impact of their initiatives addressing digital inclusion. Through an open government approach, administrations play a fundamental role regarding data sharing and promoting cooperation at the local levels. Most importantly, all people should be empowered to create, own and leverage their own data through digital technology. This can be activated through making analytical tools available and affordable for individual users, while generating person-centred data policies and regulations including transparency requirements for data collection and usage across sectors.

Spotlight

The Government of Nigeria, the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada and the International Development Research Centre partnered to establish the Nigeria Evidence-Based Health Systems Initiative (NEHSI). This initiative was committed to supporting the primary healthcare sector in two Nigerian states by improving their health information systems and developing evidence-based health planning by building sufficient capacity to capture data accurately and timely. [86]

Commit to a pledge on our Pledging Platform here. See guidelines on how to make your pledge in Pledging for Universal Meaningful Connectivity and examples of potential P2C pledges here

Footnotes

[68] GSMA. (2021). The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2021.

[69] GSMA. (2021). The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2021.

[70] GSMA. (2021). The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2021.

[71] ITU. (2021). Regional and global key ICT indicators.

[72] Gobierno de México. (2015). ¿Qué es Prospera Digital?.

[73] Action Coalition Technology and Innovation for Gender Equality. (2022). 25 years since the World Conference on Women in Beijing, the world has witnessed two things: a global digital revolution and not a single country having achieved gender equality.

[74] GSMA. (2021). The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity 2021.

[75] GSMA. (2021). The Mobile Disability Gap Report 2021.

[76] GSMA. (2021). The Mobile Disability Gap Report 2021.

[77] National Disability Authority. (2020). The 7 Principles.

[78] HearColors. (2019). Productos y servicios de accesibilidad.

[79] UNICEF. (2022). Protecting children online.

[80] NCMEC. (2020). CyberTipline 2020: Rise in Online Enticement and Other Trends from Exploitation Stats.

[81] ITU. (2021). Global Cybersecurity Index 2020.

[82] MTN. (2019). MTN partners with Internet Watch Foundation to make the Internet a safer place for children.

[83] GSMA. (2020). The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2020.

[84] GSMA. (2021). The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2021.

[85] ITU. (2021). Global Cybersecurity Index 2020

[86] IDRC CRDI. (2014). Nigeria Evidense-based Health System Initiative (NEHSI).