From roving Mars to delivering aid: AI, satellites, and UAVs in humanitarian action

By ITU News

Hundreds of millions of kilometres from Earth, exploratory drone Charity spots a feature of scientific interest on the Martian surface. Through rapid data transfers, she summons her lightweight rover companion, Perseverance, to investigate.

According to Armin Wedler of the German Aerospace Center (DLR), automated planetary exploration methods like those pioneered by recent Mars probes are proving useful in Earth’s disaster areas and conflict zones.

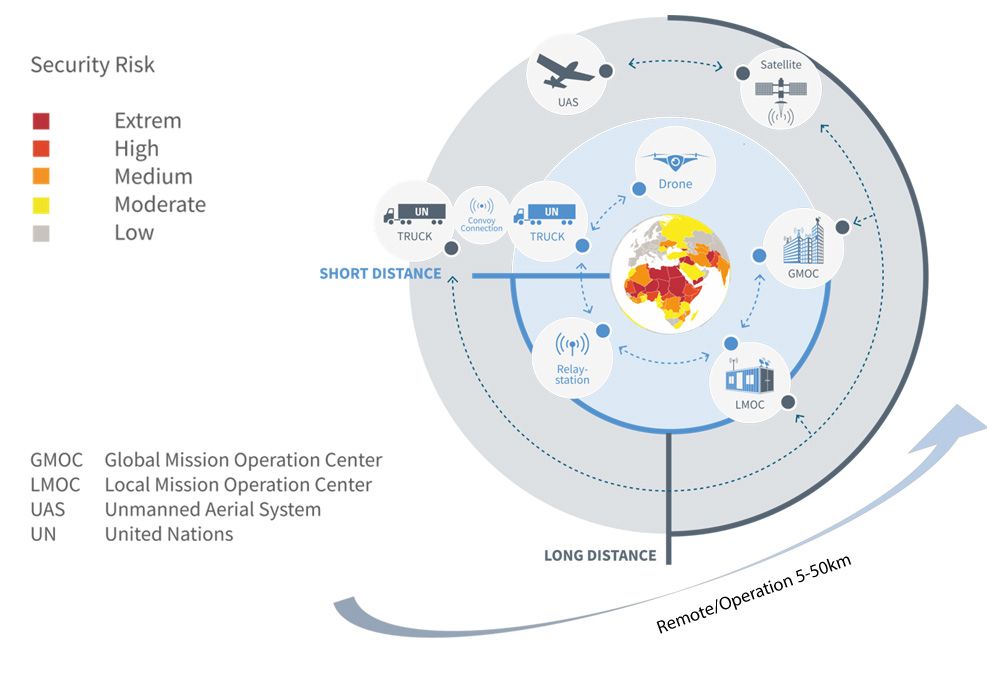

Hence Projekt AHEAD – for Autonomous Humanitarian Emergency Aid Devices. The DLR humanitarian project feeds Earth observation satellite data to remote-controlled vehicles.

This Martian-inspired application of artificial intelligence (AI), satellite data links, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) expands the delivery area for relief and assistance, especially during the highly dangerous “last-mile” leg of humanitarian supply chains, explained Wedler during a recent AI for Good webinar.

Getting AHEAD with UAVs

Equipped with 360-degree cameras and LiDAR technology, Projekt AHEAD vehicles can drive – and even swim – autonomously in harsh environments.

A landing pad atop each vehicle enables accompanying drones get a bird’s eye view to protect rescue workers potentially exposed to danger during humanitarian aid deliveries.

“Critical rescue operations can deploy UAVs to overcome shortcomings in infrastructure in inaccessible locations,” pointed out Bilel Jamoussi, chief of standardization study groups at the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

These “mechanical saviours” bring the necessary flexibility and efficiency to disaster areas and conflict zones for surveying damage, identifying survivors, and delivering relief, from food to critical supplies, he added.

DEEP damage assessment

After Cyclone Idai hit Mozambique in 2019, WFP’s rapid disaster mapping operation deployed drones for the first time, allowing damage assessments in days rather than weeks.

“In just three days, locals were trained to use 10 different drone systems to capture more than 17,000 high-resolution images to inform relief operations,” explained Annalisa Conte, Director of the Geneva office of the World Food Programme (WFP).

A digital engine for emergency photo analysis (DEEP) also made its debut there, using high-resolution images from satellites and drones to identify damaged buildings with 85 per cent accuracy within hours, lowering field operation costs.

The system appeared again in Colombia and the Philippines, as well as after the August 2020 port explosion in Beirut, Lebanon.

Maximize impact, minimize risk

Neural networks need a lot of training data to continually improve their interconnected AI systems – more than is available either in space or in disaster areas or conflict zones, said Wedler of DLR’s Projekt AHEAD.

WFP tackles this data scarcity through a global network of call centres, which collect information on food supply and hunger daily. The resulting data feeds into predictive machine learning models, which generate real-time forecasts.

Using this global hunger monitoring system, the organization can predict the magnitude and severity of hunger across 90 countries at any given time, said Conte. The resulting real-time forecasts enable humanitarian teams to address all forms of hunger more effectively, she added.

Even places lacking infrastructure and data collection resources figure on WFP’s live HungerMap, together with information on hazards and conflict zones. The open-source project makes granular, contextual food security data available to anyone with an Internet connection.

Ethical AI interventions

Despite these benefits, extracting data from humanitarian contexts can raise ethical and privacy implications, pointed out Andrej Verity, Digital Services Lead at the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

While real-time field data can help make faster decisions, humanitarian users need to understand how to handle it, he said.

“In conflict zones such as Yemen or Ukraine, this data could be sensitive.”

At the same time, he added, newly introduced technologies can bring unintended risks to local populations. “Could flying medical drones in such areas be leveraged by a nefarious actor?”

A focus group on AI for natural disaster management formed by ITU, WMO and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) is looking at key standards needed for AI to monitor and predict natural hazards and disasters.

Going forward, AI standardization should also bolster the later stages of disaster response, including reconnaissance, damage assessments and recovery, ITU’s Jamoussi said.

Learn more about the ITU Focus Group on AI for Natural Disaster Management (FG-AI4NDM), open to all interested stakeholders.